Research

Social science research in business, government, universities and community organisations.

Why social science research?

Social science research expands the boundaries of knowledge and understanding. It fosters more equitable public institutions, informs effective and efficient government programs and policies, improves education programs and helps to orient industry and employment to more socially-beneficial ends. However, the realisation of such positive impacts depends on having an integrated and well-resourced ‘knowledge pipeline’.

In the social sciences, this pipeline begins with researchers. It includes universities, think tanks and other agencies that provide the leadership and infrastructure; the publishers and data agencies who review, print, store and disseminate research data and findings; consulting firms (large and small), think tanks (again), communications professionals and researchers who translate research findings into accessible and targeted inputs; and the policy-makers, business people, NGOs and active citizens who ultimately act on these findings to elevate the quality of our lives and institutions.

This section examines the health of the Australian social science research system: what we’re doing well, where we’re lagging, and the challenges that need to be tackled next.

“The social sciences don’t have the kind of technological breakthroughs that STEM can show, that have transformed our lives. I think we struggle to articulate the contribution that we make. Climate change, COVID, AI and all the new technologies are presenting new challenges, which means we have to re-articulate and demonstrate our value. It’s basically an existential state for the social sciences.”

Executive Dean, School of Business and Law at an Australian university.

Current state

Research scorecard

Value

Quality and relevance of social science research

Performing

Consistent disciplinary performance on excellence metrics and researcher recognition.

Lagging

Commercial partnerships with industry relatively uncommon, and very little commercialisation income from research-derived products and services.

Critical

Falling behind STEM and health and medical disciplines in Excellence in Research for Australia (ERA) assessments

Priorities:

- Understand why social science is falling behind in the ERA assessment.

- Design research quality and impact metrics appropriate for the social sciences and advocate for their implementation.

Capability

Research workforce, funding and infrastructure

Performing

Diverse and skilled research workforce.

Lagging

- Limited tradition of multidisciplinarity and collaboration at scale.

- Limited preparedness for impact of AI, machine learning and digital technologies on research.

Critical

Very high reliance on ARC grants for research funding.

Priorities:

- Systematise training and support for alternative revenue generation.

- Understand and prepare for the impact of AI and data technologies on social science research, including research training in digital and data literacies

Equity

Gender equity, cultural diversity and accessibility of information

Performing

Gender equity in research workforce participation.

Lagging

Continued underrepresentation of Indigenous researchers.

Critical

Most academic research outputs are still published in subscription journals (only accessible to university staff).

Priorities:

- Introduce incentives to translation across the research pipeline, to increase social science impact on government, industry, the community sector and everyday Australians.

Value

Does Australia produce valuable social science research? Value can be examined from two perspectives: quality, or the rigour, objectivity, or originality of the research; and impact, for example, whether it provides benefit through informing public policy or other means.

Quality. Australian social science researchers produce high-quality research. 84% of social science units of evaluation were rated at or above world standard in the most recent Excellence in Research for Australia (ERA) report (2018), and Australian social scientists are over-represented (by population) on highly-cited researcher indices in many fields.

However, the same ERA reports show an increasing performance gap over the past decade between social science and STEM and Health and Medical research in Australian universities. This issue is further explored in What’s holding us back. It could reflect a real difference in quality, a result of the peer-review vs citation-based methods used to assess HASS and STEMM disciplines, or it could be a combination of the two. Understanding and addressing this issue is a priority for the social science, as well as the Humanities and Arts disciplines.

Impact. Social science research has produced and informed some of the most significant social and economic policies and programs in Australia’s history, from our globally innovative income-contingent higher education loan scheme (HECS/HELP), to water sharing policy, child-support payments and the energy rating labels that adorn household appliances. Demonstrating this impact in a consistent way is, however, challenging, as social science research generally produces knowledge and processes, rather than tangible products and services.

Further, social science knowledge can often be accessed and applied directly by people in policy or decision-making roles (many of whom are social science professionals or people with social science training) without further interaction with the researchers.

Industry funding or commercial revenue are often used as proxies for impact; the basis being that organisations, governments and consumers will pay for things they find valuable and can use. However, unlike in STEM or health and medical research, there isn’t a strong tradition of commercial partnerships between social science and industry, and there is very little commercialisation income from research-derived products and services (most of which aren’t patented and are made freely available as public goods).

While Australian governments do invest heavily in social science-based advice, the majority of this activity occurs in the context of private consulting and advisory companies with no direct links to the academic research sector. This relative lack of industry funding and non-grant government funding for social science research presents a significant challenge when it comes to demonstrate impact. It also limits the volume of social science research that could be undertaken, if additional funding and revenue streams were expanded. See What’s holding us back.

“Our research is interesting, fascinating and important. Each year teaching first-year sociology students, I’m reminded that what we do is important. It changes lives. We need to keep believing in our project and communicate to a wider audience our importance and relevance.”

Mid-career academic, Sociology, University of Tasmania.

Capability

Research workforce. Social scientists comprise 36% of Australia’s university research workforce; over 27,800 FTE in 2018. Only a small percentage of these are casual academics (7%), however more than one in five (22%) contribute their time as volunteers (often emeritus) or as unpaid collaborators.

Stakeholders identified two key pressure points for research workforce capability: (1) increasing demands and decreasing security (discussed in the previous section, No guarantees in academia); and (2) overall reductions in workforce, owing partly to the pandemic and partly to ongoing change and restructuring in the higher education sector.

Funding. Investment in social science research in Australia amounts to around $1 billion per year, across multiple funding sources and beneficiaries. Universities’ social science research income totalled $878m in 2016 (ARC 2018), obtained through competitive grants (40%), other public sector funding (42%), industry (16%) and Cooperative Research Centres (2%). Meanwhile, expenditure in social science R&D was roughly $3.3m per annum (ABS 2018-20) (this includes expenditure by higher education institutions, but also government, businesses and private non-profits).

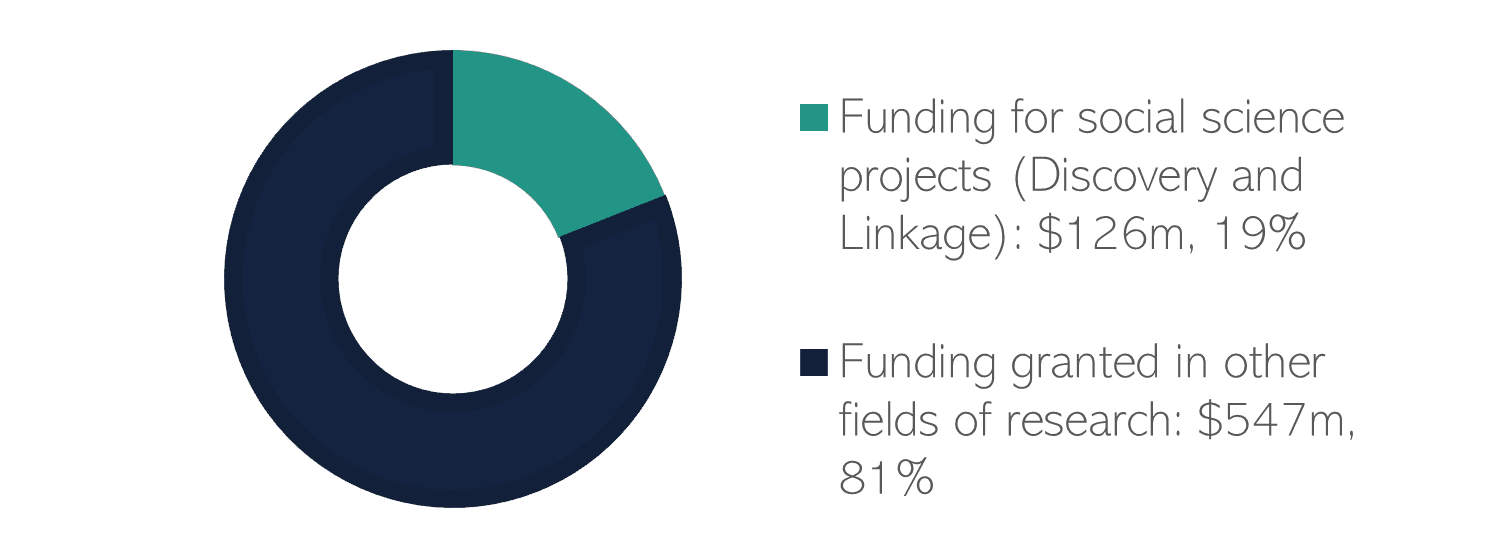

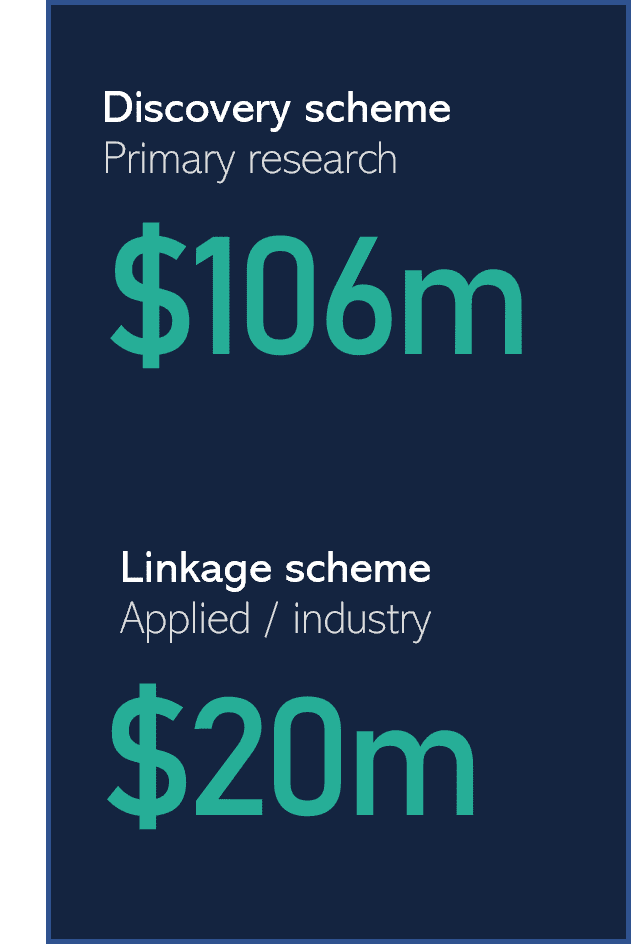

Although this is a substantial investment that supports high-quality research, social science disciplines lag the STEM and health and medical fields in the allocation of competitive research funding. For example, social science research secured approximately 19% of total ARC grant funding in 2021 despite comprising over 40% of the eligible applicant pool (excluding medical research).

Furthermore, ABS data shows that between social science research secured just over 10% of total annual R&D expenditure in Australia.

While it is true that most social science research doesn’t need the specialised and costly instrumentation and materials often required for STEM and health and medical research, the majority of non-capital research funding (research operations, rather than infrastructure) are allocated to staffing across all disciplines. The relative lack of funding for social science research therefore represents a disproportionate constraint on research capability; limiting valuable work that could be done. Further, given that much of the available research funding is allocated through competitive processes, existing gaps between disciplines typically increase over time as less successful disciplines and fields progressively lose capacity to compete. Combined with the other financial pressures facing universities, stakeholders reported that many schools are already struggling to maintain sustainable levels of research activity, and in some cases are choosing to shift academics into full-time teaching instead.

Research infrastructure. A number of current initiatives have the potential to enhance social science research infrastructure. These include the pending 2021 National Research Infrastructure Roadmap, and the recently launched HASS and Indigenous Research Data Commons project. The latter explicitly aims to fast-track the evolution of social and cultural data systems in Australia, supported by an investment of $8.9 million over four years.

Competitive research grants, social science, 2021

Based on ARC (2021). Social science totals were obtained from adding up the following 2-digit Fields of Research: Built Environment and Design; Education, Economics; Commerce, Management, Tourism and Services; Studies in Human Society; Psychology and Cognitive Sciences; Law and Legal Studies; Language, Communication and Culture; History and Archaeology; and Philosophy and Religious Studies.

“We need bigger social science research projects that tackle big issues. ARC grants of $400,000 over 3 years allow for the career development of one postdoc and not much else. Where are the big teams working on fundamental societal issues? We need more EU type and scale grants that work on basic social science issues.”

Senior academic, Policy and Administration, University of Melbourne.

Equity

Equity in research covers multiple domains: gender representation and representation of other diversity groups, as well as equity in access to research findings.

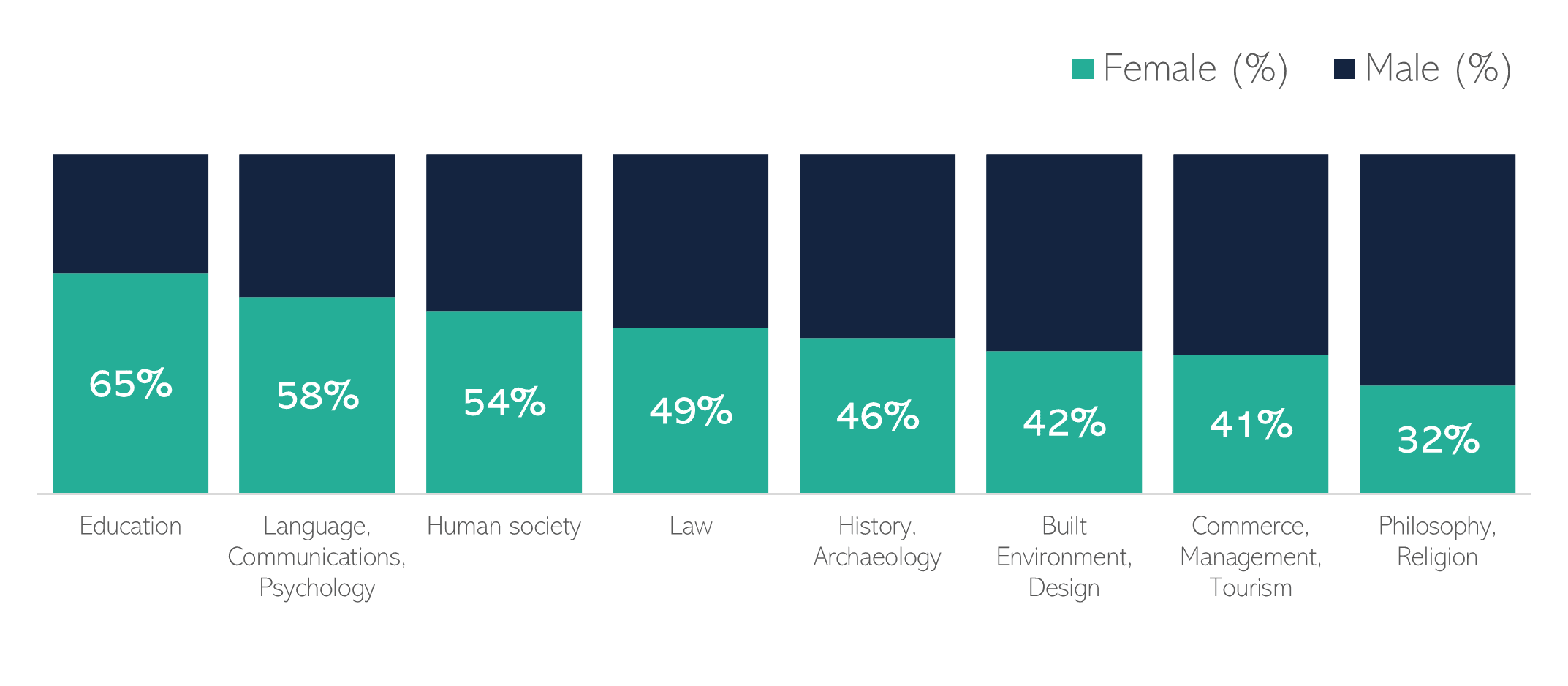

Gender equity. There are as many men as women employed as social science researchers in Australian universities (12,858 women and 12,890 men in the 2018 ERA report), although there is substantial variation across disciplines.

As in all research fields, however, historic and continuing barriers to participation and advancement for women mean that men outnumber women at senior academic levels. As universities and research funding agencies get better at removing systematic gender biases in recruitment, award and promotion processes, it is likely that this seniority gap will reduce further.

Cultural and other demographic diversity. Unfortunately, there is no systematic data on cultural and linguistic diversity (CALD), disability or GLBTI representation in research disciplines. Noting that such data is hard to collect, stakeholders reported that the social sciences are predominantly white and Western in their composition and in their approach. As noted in the First Nations snapshot, Indigenous Australians are underrepresented in the social sciences; comprising less than 1% of the research workforce.

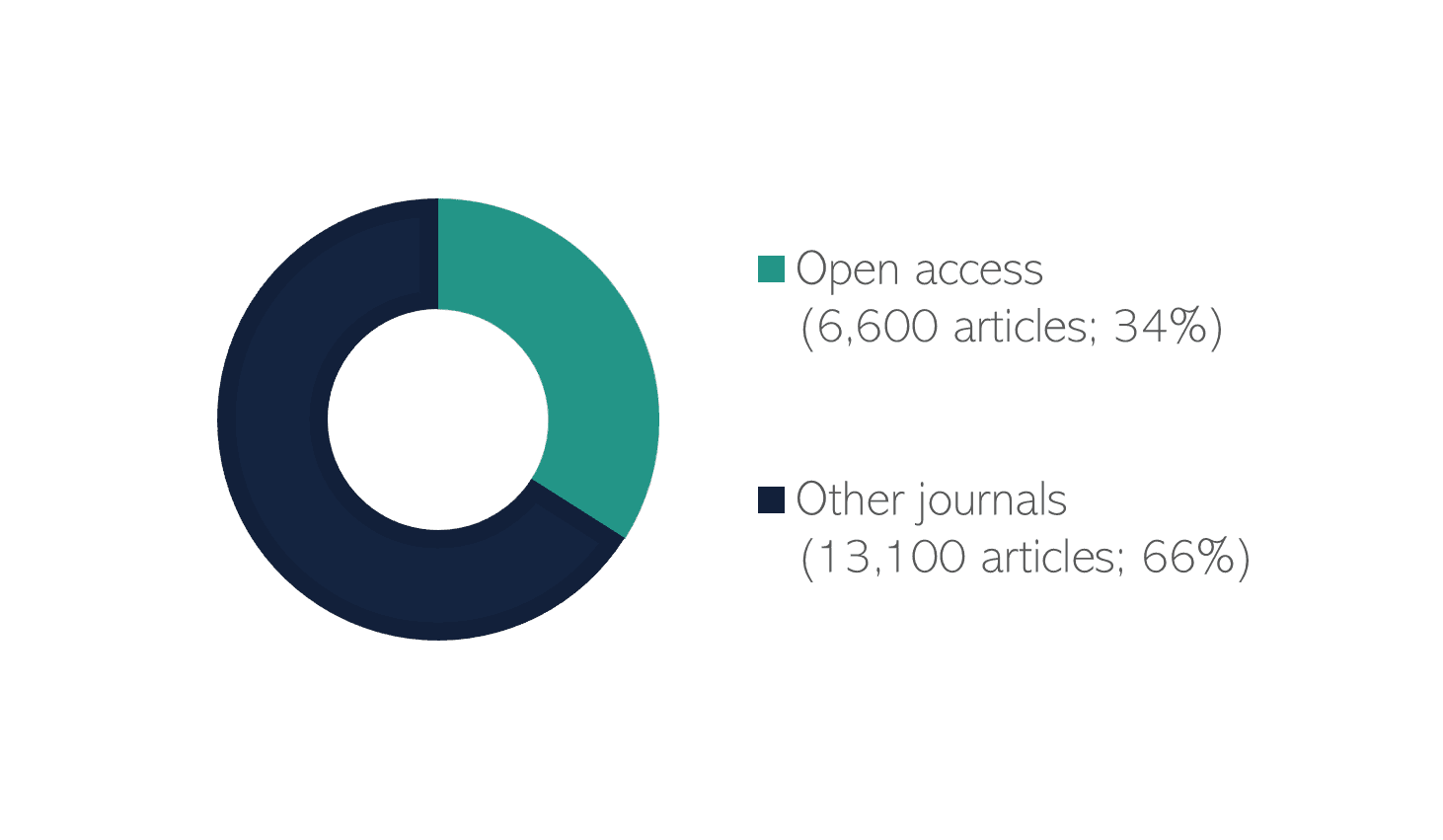

Equity of access to research outputs. Most academic research outputs are still published in subscription journals that are effectively exclusively accessible to university staff and students, and to some research institute employees. An accelerating shift towards open access publication is helping to overcome this issue (albeit not without other costs and challenges for researchers), with social science researchers in Australia rapidly adopting open access practices.

Social science articles in open access journals, 2020

Based on a Scopus search (August, 2021). Includes: subject areas (social science, business, economics and psychology); document type (article); country of affiliation (Australia).

Female researcher participation in social science, 2018

Based on ARC (2018)

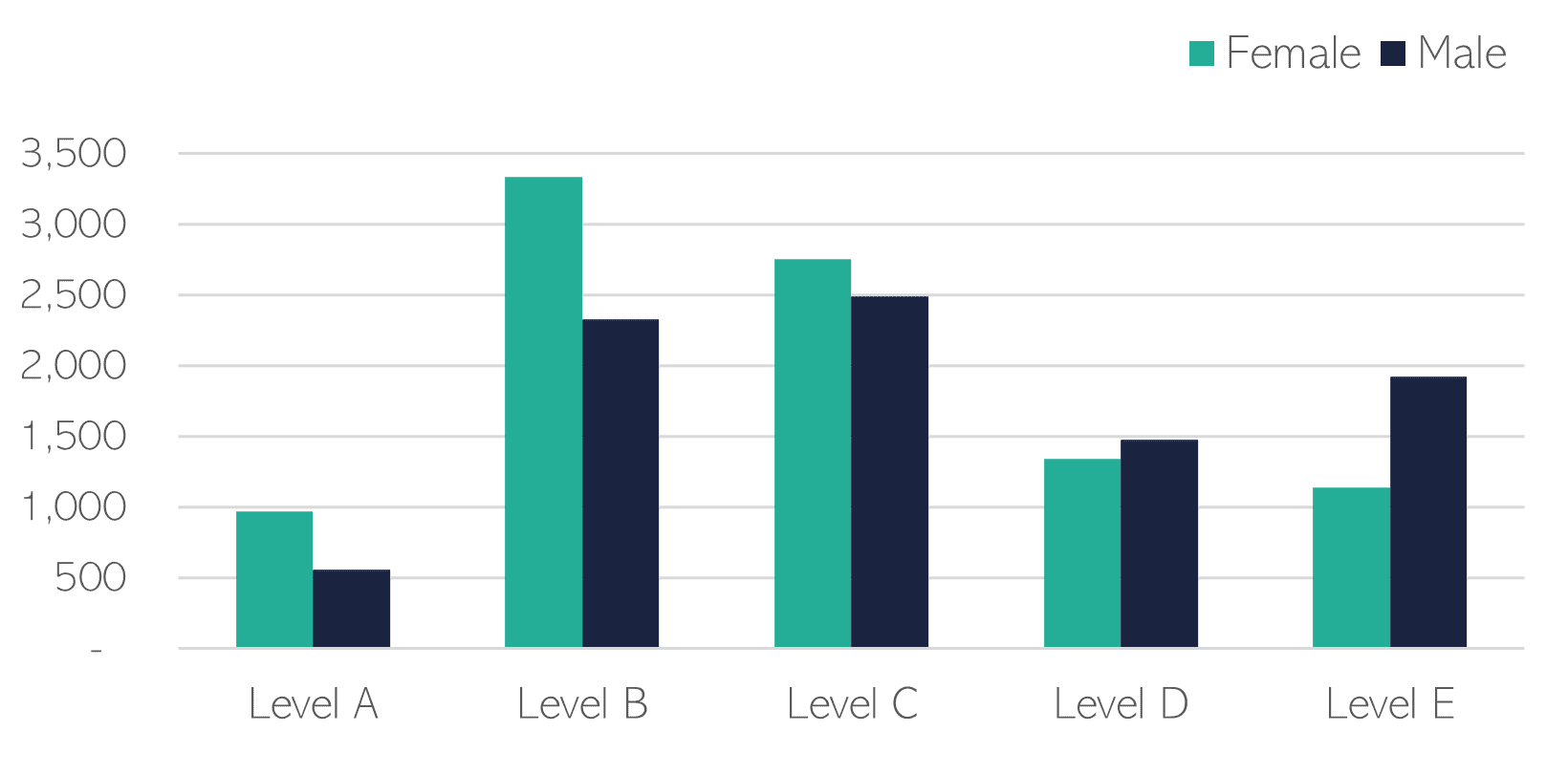

Gender representation by academic level, social science researchers (FTE)

Based on ARC (2018). Level A: Associate Lecturer; Level B: Lecturer; Level C: Senior Lecturer; Level D: Reader or Associate Professor; Level E: Professor.

Priorities for action

1

Understand why social science is falling behind

In the ERA assessment.

2

Design research quality and impact metrics

That are appropriate for the social sciences and advocate for their implementation across the ecosystem.

3

Systematise training and support for alternative revenue generation

4

Understand and prepare for teh impact of AI and data technologies on social science research

Including through research training programs to boost the digital and data literacy of social science researchers.

5

Introduce incentives to research translation

Across the research pipeline; to increase the volume of, an speed at which social science research reaches decision-makers; from government, to industry, to the community sector, to the media, to the everyday Australian.

Data sources

Percentage of social science units of assessment rated at or above world standard based on: ARC (2018) ERA Outcomes, https://dataportal.arc.gov.au/ERA/Web/Outcomes.

Number of social science researchers and appointment types from: ARC (2019) State of Australian University Research 2018–19: Volume 1 ERA National Report, Australian Research Council, Canberra (Staffing Profile, dataset), https://dataportal.arc.gov.au/ERA/NationalReport/2018/pages/section4/staffing-profile/.

Total ARC grant funding awarded in social science fields of research and other fields, from: ARC (2021) National Competitive Grants Program Dataset (spreadsheet), https://www.arc.gov.au/grants-and-funding/apply-funding/grants-dataset.

Analyses of female researcher participation in the social sciences, by discipline and academic level from: ARC (2018) Excellence in Research For Australia, ERA, Gender and the Research Workforce, https://dataportal.arc.gov.au/ ERA/GenderWorkforceReport/2018/.

Count of social science research articles published in Open Research and other academic journals from a Scopus database search performed in August 2021. Results filtered by subject area (social science, business, economics and psychology), document type (article), and country of affiliation (Australia).

Research income reported by universities from: ARC (2018) State of Australian University Research 2018–19: Volume 1 ERA National Report (Section 4, multiple datasets). https://dataportal.arc.gov.au/ERA/NationalReport/2018/.

Expenditure in Research and Experimental Development across government, higher education, businesses and private non-profit from: ABS (2018-20) Technology and innovation, various datasets, https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/technology-and-innovation.

Department of Industry, Science, Energy & Resources, DISER (2021) 2020-21 SRI Budget Tables. https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/science-research-and-innovation-sri-budget-tables.