The skills conundrum

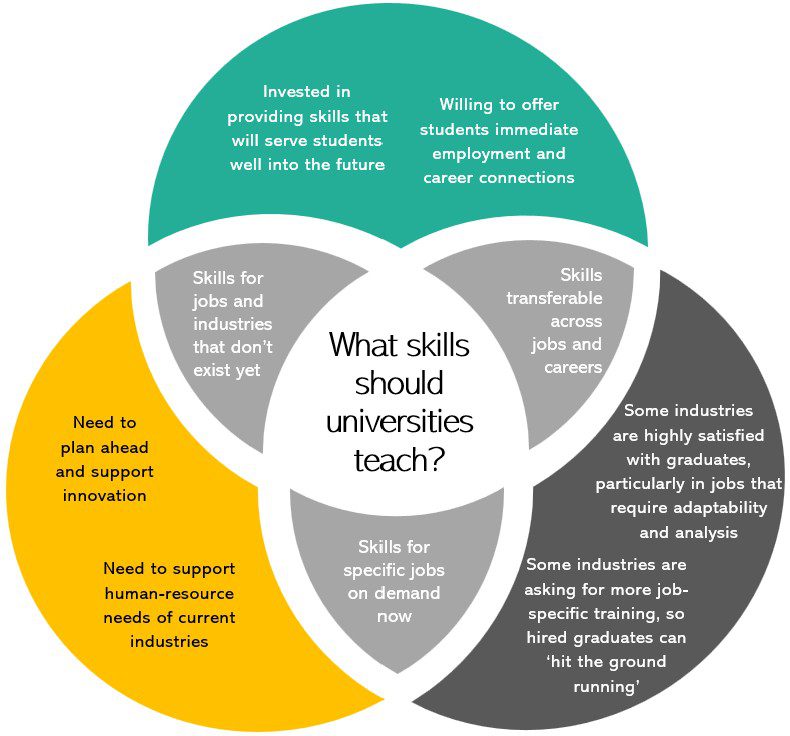

University teachers across all disciplines, including the social sciences, are feeling pressured by the government to dedicate more of the curriculum space to job-specific skills training. University management is likely to follow suit, as job-readiness is an easy selling point. But are job-specific skills the best use of the university experience? A problem that appears as a simple dilemma between job-specific vs. career-transferable skills is actually complicated by several other variables.

Read on for a glimpse of the complexities raised during the consultation process. Finding alternatives that deliver the best possible outcomes for students will require a whole-system coordinated approach.

Where might universities be falling short?

Underselling industry

“[Social science] graduates have said ‘I only want to work in an NGO or government’, when they could be doing amazing work in the private sector, with people who are also passionate about their purpose and making a difference. We need to teach social sciences in a way that broadens students’ perspectives about the opportunities available in the private sector.” Policy manager, mining industry.

“We’ve got a booming film industry. People studying computer science see a future in it (working in CGI, for example), but our writers and historians don’t. The links are obvious to us [academics], but the community doesn’t get it. There is a real need for that conversation”. Senior academic, Psychology.

Explicitly discussing real-world utility or social science skills

“We need to talk about what the distinctive methods are in the social sciences, so that students understand what they’re actually getting […]. As much as I don’t think university education is just for employability, that is something we have to really engage with. Otherwise [social science] just becomes almost like a generalised way of thinking.” Senior academic, Western Sydney University.

Problems on the horizon in industry?

Ever-climbing stakes to entry-level jobs

“Years ago, you could get an arts degree and walk into the public service. That bar has been lifted. Now you need a double degree, a master’s and then a few years of experience.” Senior employee, Australian Government.

“Often, people who’ve applied for a job with a PhD qualification tell us they got it because after their undergraduate degree they couldn’t get a job. So they went: “I’ll heighten that with master’s or PhD”. And… it becomes a cycle”. Executive director, government agency.

Erosion of industry training opportunities

“When I was an undergraduate, there were cadetships and studentships, which seem absent from the scene now. Industry has stopped training. Universities provide some work-integrated learning, but that’s still not the industry doing the training, or something universities will be able to teach. And it’s causing all sorts of problems for people trying to get started in an industry. That’s a major missing piece in our country’s training system.” Senior academic, University of Western Australia.

”It is becoming acceptable for students to work in unpaid internships for years.” Senior academic, Psychology.

Where might the government be getting it wrong?

Public support for the social sciences

“The government conversation for the last 20 years has been negative about the role of expertise in guiding policy. And that affects more negatively the social sciences, than it does STEM. We need recognition that the social sciences have important things to offer.“ President, social science association.

Asking universities for job-readiness

“The Job-Ready focus sells universities short in their purpose. While preparing graduates for professions is a part of their mission, it is well short of educating them in the broader sense. Also, there can never be one-to-one correspondence between university programs and the diverse range of roles that graduates fill. You just have to look at the range of roles where graduates of single programs end up.”

Senior Academic, Education, UQ.