First Nations

The historical impact of the social sciences on Australia’s First Nations peoples has been damaging, with harm continuing even to this day.

The social sciences have:

- Contributed to the marginalisation of Indigenous individuals and communities, as much of the research about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples has and continues to be focused disproportionately on deficits over capabilities.

- Created barriers to Indigenous involvement in mainstream education and research, resulting in inappropriate recognition, understanding and incorporation of traditional and contemporary First Nations knowledges. Western knowledge systems and structures have dominated mainstream teaching and inquiry, including the very study of First Nations peoples and communities.

- Separated communities and individuals from stewardship of their data.

- Placed an enormous weight of expectation on the few First Nations researchers and teachers in leadership positions in social science institutions.

“There’s a danger of us being distracted and missing the living indigenous Academy on this continent, which is passing away with every passing language. We’re still losing languages, we’re still losing elders […]. There are senior knowledge holders scattered across this continent, who should be our absolute priority, if we’re going to do more than just pay lip service and have sexy conversations about [Indigenous engagement].”

Senior Indigenous researcher, University of Tasmania.

Current state

First Nations scorecard

Value

Appreciation and dissemination of

Indigenous knowledge.

Performing

Formal recognition of Indigenous issues as a Field of Research.

Lagging

Incorporating First Nations content in schools, VET and university curricula.

Critical

Building capability in both Indigenous and non-Indigenous academic workforce, to teach Indigenous content.

Priorities:

- More and better-quality Indigenous content in schools, VET and university; and staff appropriately trained to teach it.

- Nation-wide data infrastructure and protocols that give Indigenous Australians control over Indigenous data collection, access and use.

Capability

Institutional support to enable inclusion.

Performing

Efforts to enhance Indigenous capability, such as the establishment of AIATSIS.

Lagging

Unsustainable mechanisms for Indigenous capability building leading to staff and elder burnout.

Critical

Lack of scale and infrastructure to preserve Indigenous culture means Indigenous languages and culture are being lost every day.

Priorities:

- New and enhanced infrastructure and programs to preserve First Nations peoples’ knowledges.

- Programs and support for First Nations Australians to pursue social science study and careers.

- Increased recognition of Indigenous social scientists through proactive nomination for relevant awards and election to the Academy.

Equity

Accessibility, diversity

and fairness.

Performing

–

Lagging

Poor awareness of persisting racism and disadvantage in the education and academic sectors.

Critical

High individual costs (time, career) for Indigenous staff who seek to increase institutional capability.

Priorities:

- Practical improvements to the wellbeing and careers of Indigenous Australians in the education and research sectors.

Value

First Nations and non-Indigenous stakeholder consultations showed a clear consensus on the need to improve the representation and involvement of Indigenous Australians at all levels of education, research and leadership in the social sciences.

There was also agreement about the significant and inherent value in the recognition, expansion, inclusion, celebration and dissemination of traditional and contemporary First Nations knowledge within and across the disciplines.

This is the unique and irreplaceable knowledge and understanding of people and society that has been developed and passed down over millennia, as well as the knowledge developed by First Nations people living in and interacting with the complex cultural and social structures of the modern world.

Indigenous Australians in the social science sector

Based on data from the NCVER (2020), DESE (2019) and ARC (2020)

VET |

UNIVERSITY |

RESEARCH |

|

|

|

Capability

Stakeholders agreed that there has been some progress, albeit insufficient, towards improving First Nations capability at individual and organisational levels in the social science sector.

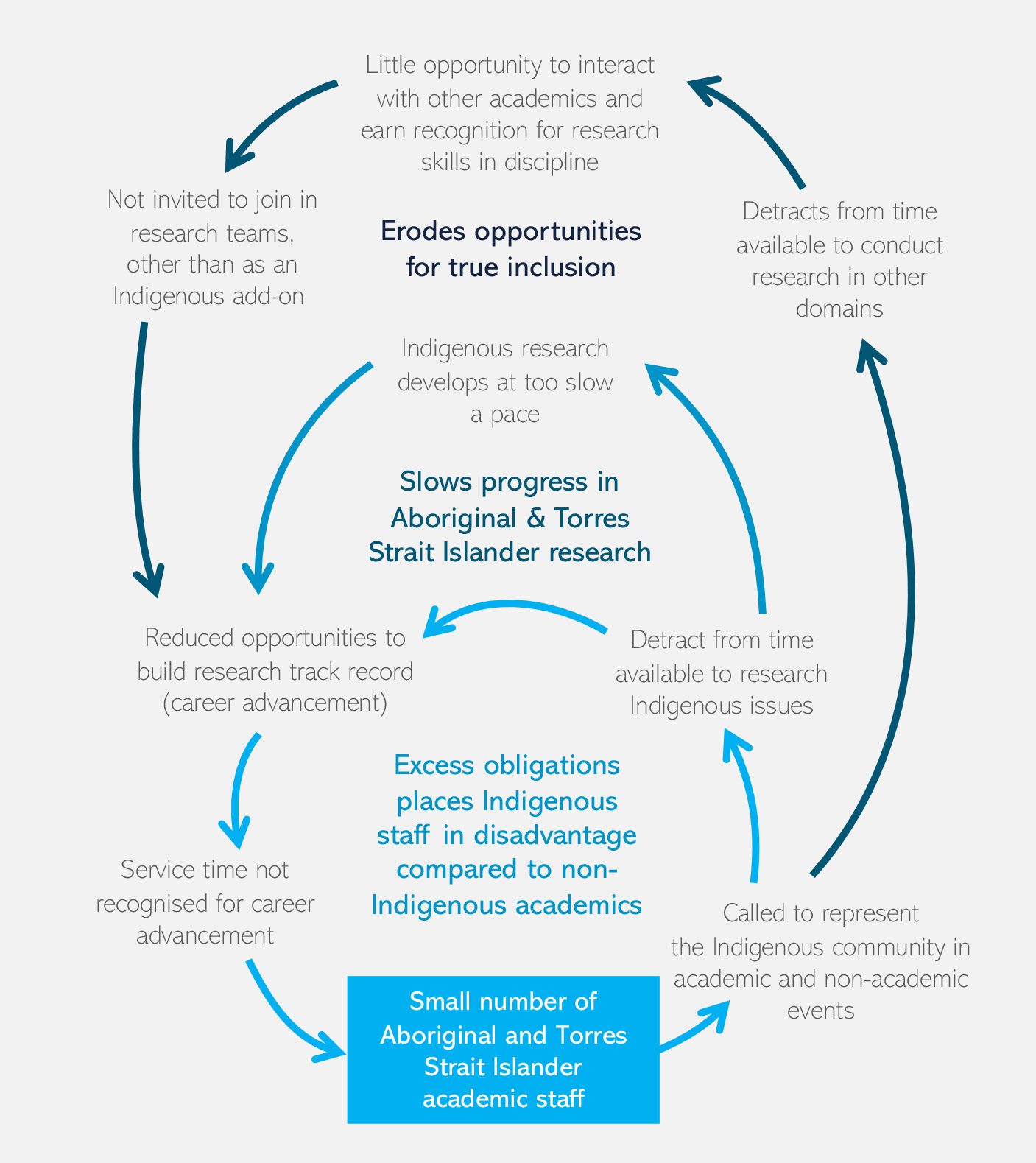

In part, the lack of current capability is related to the small number of First Nations people in the social sciences and the often overwhelming demands on those few in senior and leadership positions.

It also relates to the lack of capacity of traditional institutions to effectively incorporate and work with alternative education and research paradigms that incorporate First Nations knowledge and practices, despite good intentions and goodwill on the part of many individuals.

Finally, the lack of coordinated national infrastructure and frameworks to support and enhance participation of First Nations people and knowledge is a barrier to more effective engagement and inclusion, although this is changing over time.

Equity

Active and passive discrimination and racism against First Nations people and communities have had a profound and continuing impact on equity of opportunity and involvement in the social sciences. Alongside underrepresentation of First Nations peoples across the social science ecosystem, manifestations of this inequity include:

- Deficit focus. Social science teaching, research and policy often emphasise the lower average status or outcomes of Indigenous compared to non-Indigenous peoples on a range of social measures. While important and necessary in some cases–the Closing The Gap targets an example–such aggregated data hides the enormous diversity among Indigenous people and communities, and portrays First Nations people as being generally disadvantaged.

Without appropriate context, such data can even imply First Nations peoples as complicit in ‘their problems’, and glosses over the fact that there is the potential for completely different standards of progress from an Indigenous viewpoint. A balanced approach is important: acknowledging and measuring differences, as well as the diversity of Indigenous language and cultural groups, and the role of the colonial process in creating a sense of competition.

- Lack of recognition of Indigenous expertise in non-Indigenous matters. The expertise of Indigenous academics in non-Indigenous research areas gets little attention among academic staff at universities. Indigenous scholars get consulted frequently on Indigenous matters but are rarely invited to join academic projects in their capacity as experts in other fields. Stakeholders with personal experience of this phenomenon reported that this leads to feelings of isolation and under-recognition, limited career opportunities, and ultimately undermines opportunities for true diversity, and the potential benefits this has for Australian research.

- Colonial institutions and curricula. Education and research spaces have been largely shaped by Western influences, without regard to First Nations cultures and values. Identifying practical ways to transform education and research institutions into welcoming spaces for Indigenous Australians is our shared responsibility (see Reconciliation and the social sciences).

"I’ve spent most of my academic career building capacity within the institutions, as do other Indigenous academics. We see high levels of burnout, and it’s not acknowledged in our workloads, career progressions, or staff development. The same happens with knowledge holders in the community."

Senior Indigenous researcher at a regional university.

Priorities for action

1

Enhancing the quality and availability of Indigenous content

in schools, VET and university; and improving academic staff skills to teach Indigenous content appropriately.

2

National-scale Indigenous data infrastructure and protocols

that guarantee Indigenous Australians can determine what data is collected about them, how it is collected, and oversee its access and use. Incorporate these into new and existing data collections and regulation, with training and compliance mechanisms for all involved in collecting, storing, disseminating or utilising Indigenous data.

3

Preserving First Nations knowledges,

through new and existing programs and infrastructure, designed and governed by and with First Nations peoples.

4

Measuring, supporting and advocating for increased participation

of Indigenous Australians in social science education and research. This requires additional supports, alternative entry and progression pathways, culturally-safe systems and environments, institutional and individual commitments to reconciliation, and a focus on ensuring critical mass for First Nations students and employees.

5

Increased recognition of Indigenous social scientists

through proactive nomination for relevant awards and election to the Academy.

6

Staff programs

that appropriately support and reward Indigenous research and careers.

Data sources

Count of Indigenous student enrolments in VET from: National Centre for Vocational Education Research, NCVER (2020) Total VET students and courses 2020: program enrolments, Research and Statistics, Data Builder, https://www.ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/data/databuilder,

Count of Indigenous students and academic staff at Australian universities from: Department of Education, Skills and Employment, DESE (2019) Higher Education Statistics, Student data and Staff data, https://www.dese.gov.au/ higher-education-statistics.

Count of Indigenous Discovery Grants and total funding from: ARC (2021) National Competitive Grants Program Dataset (spreadsheet), https://www.arc.gov.au/ grants-and-funding/apply-funding/grants-dataset.